A long history

Stocks and pillories have been used in parts of Europe more than 1000 years, probably much longer in Asia, and certainly before reliable records began. The earliest recorded reference to stocks in Europe appears in the Utrecht Psalter, which dates from around 820 AD.

Stocks and pillories have been used in parts of Europe more than 1000 years, probably much longer in Asia, and certainly before reliable records began. The earliest recorded reference to stocks in Europe appears in the Utrecht Psalter, which dates from around 820 AD.

Stocks had become common in England by the mid-14th century. In 1351 a law (the Statute of Labourers) was introduced requiring every town to provide and maintain a set of stocks. This had been implemented as a reaction to the Black Death, which had halved the population. The consequent scarcity of labour had enabled agricultural labourers to demand increased pay. The Statute attempted to discourage this trend by providing that anyone demanding (or offering) higher wages should be set in the stocks for up to 3 days.

Stocks had become common in England by the mid-14th century. In 1351 a law (the Statute of Labourers) was introduced requiring every town to provide and maintain a set of stocks. This had been implemented as a reaction to the Black Death, which had halved the population. The consequent scarcity of labour had enabled agricultural labourers to demand increased pay. The Statute attempted to discourage this trend by providing that anyone demanding (or offering) higher wages should be set in the stocks for up to 3 days.

Stocks were later used to control the unemployed. The Vagabonds and Beggars Act 1494 provided that “Vagabonds, idle and suspected persons shall be set in the stocks for three days and three nights and have none other sustenance but bread and water and then shall be put out of Town.”

The Poor Law Act of 1531 directed “how aged, poor, and impotent Persons, compelled to live by Alms, shall be ordered, and how Vagabonds and Beggars shall be punished. The former were to be licensed to beg, the latter if found begging were to be whipped or put in the stocks for three days and nights with bread and water only and then to return to their birth-place and put to labour.” Click here for more information about beggars.

A Statute of 1605 required that anyone convicted of drunkenness should receive six hours in the stocks, and those convicted of being a drunkard (as opposed to be caught drunk) should suffer 4 hours in the stocks or pay a substantial fine (of 3 shillings and 6 pence). A slightly later Statute made it legal to set those caught swearing in the stocks for 1 hour, if they could or would not pay a one shilling fine. In practice the authorities preferred offenders to pay fines as the monies were used to fund poor relief.

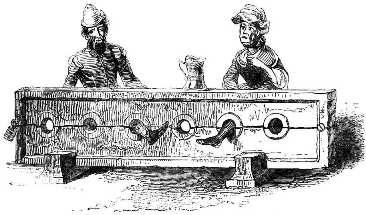

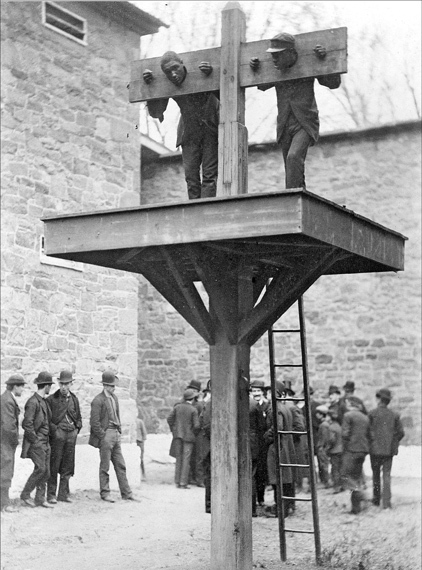

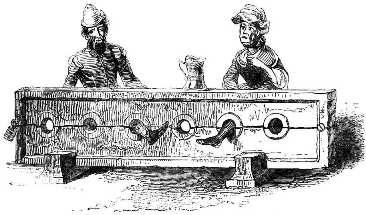

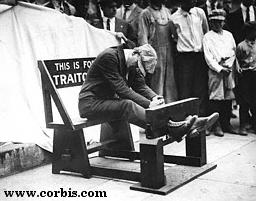

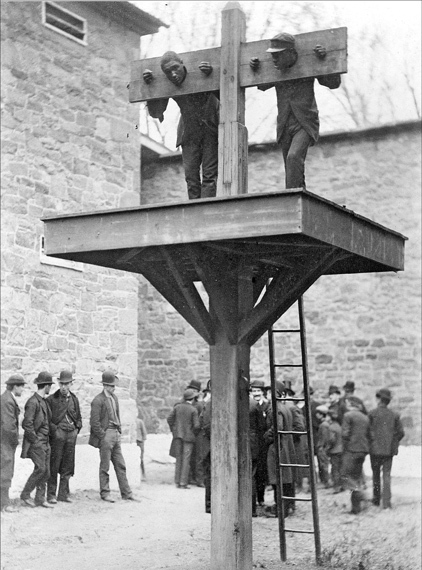

Here are some more historical illustrations:

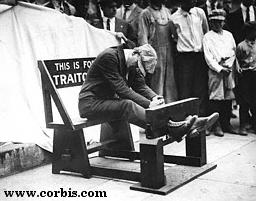

Most European countries abolished stocks and pillories by the

middle of the 19th century, as did most American states. Except

for Delaware, which was reluctant to abandon the pillory until

1905.

Abolition of the pillory

In Britain, there were attempts to abolish the pillory in the 18th century. Most notably a speech by Edmund Burke in Parliament in 1780, in which he described the adverse consequences of the pillory and argued (unsuccessfully) for its abolition.

It was not until 1816 that the use of the pillory was restricted to punishing perjurers. Here are extracts from the

Parliamentary debates of the Pillory Punishment Abolition Bill. And a scan of the original

Act of Parliament.

The last person who stood in the pillory in London was Peter James Bossy. He was tried for perjury, and sentenced to transportation to Australia for seven years.

Prior to being transported Bossy imprisoned for six months in Newgate jail and to stand for one hour in the pillory outside the Old Bailey

courthouse. The pillory part of the sentence took place on 24 June 1830.

The pillory was not finally abolished in Britain until 1837. Here is a scan of the original

Act of Parliament.

The stocks

Curiously enough, the

stocks were never formally abolished. They continued to be used, albeit

less

regularly, until the 1870s. One of the more recent cases on record was

reported in the Leeds Mercury (14 April 1860). At Pudsey, the

appropriately

named John Gambles sat in the stocks for six hours for gambling on a

Sunday.

Curiously enough, the

stocks were never formally abolished. They continued to be used, albeit

less

regularly, until the 1870s. One of the more recent cases on record was

reported in the Leeds Mercury (14 April 1860). At Pudsey, the

appropriately

named John Gambles sat in the stocks for six hours for gambling on a

Sunday.

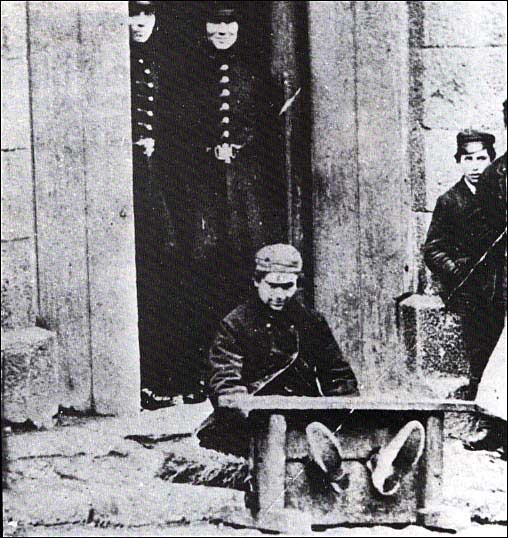

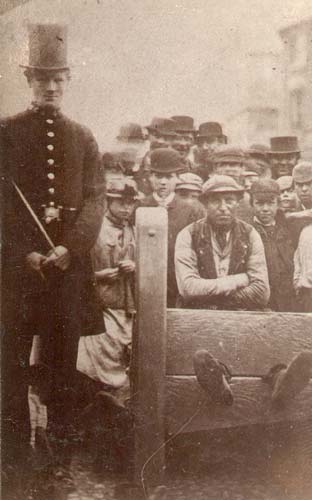

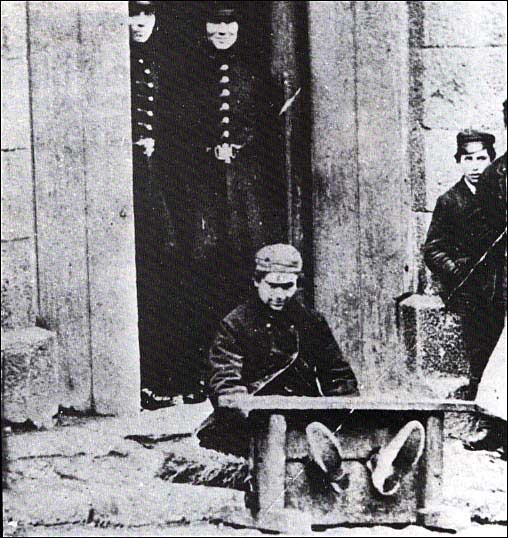

Another case involved drunkenness. In 1865 William Jarvis (see left photo) sat in the stocks in Rugby for six hours for insobriety.

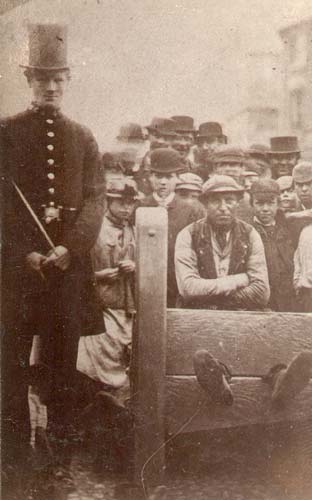

The last recorded instance of the stocks being used in England was in Newbury in 1872. According to a contemporary account, “Mark Tuck, a rag and bone dealer, who for several years had been well known as a man of intemperate habits, and upon whom imprisonment in Reading gaol had failed to produce any beneficial effect, was fixed in the stocks for drunkenness and

disorderly conduct in the Parish Church on Monday evening. Twenty-six years had elapsed since the stocks were last used, and their reappearance created no little sensation and amusement, several hundreds of persons being attracted to the spot where they were fixed. Tuck was seated upon a stool, and his legs were secured in the stocks at a few minutes past one o’clock, and as the church clock, immediately facing him, chimed each quarter, he uttered expressions of thankfulness, and seemed anything but pleased at the laughter and derision of the crowd. Four hours having passed, Tuck was released, and by a little stratagem on the part of the police, he escaped without being interfered with by the crowd.”

The Village Lock-up Association

The Village Lock-up Association has conducted a comprehensive survey of lock-ups and various other historical punishment devices in the UK and, to a lesser extent, the USA. Here is an extract from that survey covering stocks, pillories and similar punishments.

[Return to index page]

Last modified 3 June 2021.

Copyright © StocksMaster. All rights reserved.

Stocks and pillories have been used in parts of Europe more than 1000 years, probably much longer in Asia, and certainly before reliable records began. The earliest recorded reference to stocks in Europe appears in the Utrecht Psalter, which dates from around 820 AD.

Stocks and pillories have been used in parts of Europe more than 1000 years, probably much longer in Asia, and certainly before reliable records began. The earliest recorded reference to stocks in Europe appears in the Utrecht Psalter, which dates from around 820 AD.

Stocks had become common in England by the mid-14th century. In 1351 a law (the Statute of Labourers) was introduced requiring every town to provide and maintain a set of stocks. This had been implemented as a reaction to the Black Death, which had halved the population. The consequent scarcity of labour had enabled agricultural labourers to demand increased pay. The Statute attempted to discourage this trend by providing that anyone demanding (or offering) higher wages should be set in the stocks for up to 3 days.

Stocks had become common in England by the mid-14th century. In 1351 a law (the Statute of Labourers) was introduced requiring every town to provide and maintain a set of stocks. This had been implemented as a reaction to the Black Death, which had halved the population. The consequent scarcity of labour had enabled agricultural labourers to demand increased pay. The Statute attempted to discourage this trend by providing that anyone demanding (or offering) higher wages should be set in the stocks for up to 3 days.

Curiously enough, the

stocks were never formally abolished. They continued to be used, albeit

less

regularly, until the 1870s. One of the more recent cases on record was

reported in the Leeds Mercury (14 April 1860). At Pudsey, the

appropriately

named John Gambles sat in the stocks for six hours for gambling on a

Sunday.

Curiously enough, the

stocks were never formally abolished. They continued to be used, albeit

less

regularly, until the 1870s. One of the more recent cases on record was

reported in the Leeds Mercury (14 April 1860). At Pudsey, the

appropriately

named John Gambles sat in the stocks for six hours for gambling on a

Sunday.