At the mercy of the mob

A significant drawback to stocks and pillories is that the

severity of the punishment depended much on the attitude of

the crowd. How they felt about the crime committed, whether or

not they liked the victim, or simply what mood they were in that

day.

Charles Dickens observed in “A Tale of Two Cities” that the pillory “inflicted a punishment of which no

one could foresee the extent”.

Role of the crowd

Here is an extract from "Crime, Punishment, and Reform in Europe" by Mary Anne Nichols and Louis A. Knafla, which considers the role of the crowd in relation to the pillory:

"The crowd played an important role. As a form of legally sanctioned street theatre, each pillory event relied upon the audience for its success. In a carnival-like atmosphere, people crowded the streets and surrounding buildings in an attempt to get the best vantage point to view the offender’s punishment.

As individual spectators were lured and frenzied by a certain malicious schadenfreude, the pillory could be interpreted as a true crowd-pleasing spectacle, but it was not merely a kind of theatre sport. Indeed it was didactic theatre; the pillory was meant to provide lessons and warnings for other would-be transgressors of the law.

As individual spectators were lured and frenzied by a certain malicious schadenfreude, the pillory could be interpreted as a true crowd-pleasing spectacle, but it was not merely a kind of theatre sport. Indeed it was didactic theatre; the pillory was meant to provide lessons and warnings for other would-be transgressors of the law.

Moreover crowd participation in a pillory event was an extension of the political sophistication that scholars…..have recognised in the English mob. Those who gathered round the pillory were participating in a quasi-legal ritual that was expected to denounce the individual and uphold the rule of law, as well as protect the moral standards of the community. Crowds thus became, in the final instance, both judge and jury, and their decisions were absolute.

In 1816 the use of the pillory was restricted by law, and completely abolished in 1837. This change in part reflected the development of criminal justice theory away from public punishment and towards an emphasis on the rehabilitation of the criminal. Concurrently, there was a more general rejection of violence in society, with the pillory seen by some contemporaries as an endorsed form of mob violence, anarchy and barbarity.

The unpredictability of punishment in the pillory also contributed to its demise. It had made criminal justice something of a lottery and, by the early 19th century, English administrators were no longer prepared to gamble. Unlike those convicted of sexual crimes, political offenders were often received in the pillory as heroes, thereby undermining the moral authority of the law as public prosecution turned into public recognition."

Mood of the mob

On some occasions, the attitude of the mob worked in the

victim’s favour. When the author, Daniel Defoe (above), was pilloried

for satirising the Government, the crowd was definitely on his

side. They brought him food and drink, showered him with

flower petals, and even chanted a poem composed for the

occasion, entitled “Ode to the Pillory”.

The crowd could also be remarkably lenient to less celebrated individuals, as

this contemporary newspaper report shows:

"Yesterday at Noon Sarah Thomas stood in the Pillory in the Old Bailey,

opposite to Fleet-Lane, for keeping a disorderly House, pursuant to her Sentence

at the last Quarter Session in Guildhall. The Mob behaved to her with great Humanity,

she standing on the Pillory all the Time drinking Wine, Hot-pot, &c. It was Diversion

to her rather than a Punishment." (St. James’s Chronicle 29-31 October 1761)

The crowd could also be remarkably lenient to less celebrated individuals, as

this contemporary newspaper report shows:

"Yesterday at Noon Sarah Thomas stood in the Pillory in the Old Bailey,

opposite to Fleet-Lane, for keeping a disorderly House, pursuant to her Sentence

at the last Quarter Session in Guildhall. The Mob behaved to her with great Humanity,

she standing on the Pillory all the Time drinking Wine, Hot-pot, &c. It was Diversion

to her rather than a Punishment." (St. James’s Chronicle 29-31 October 1761)

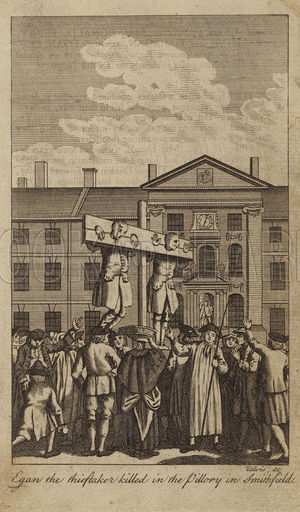

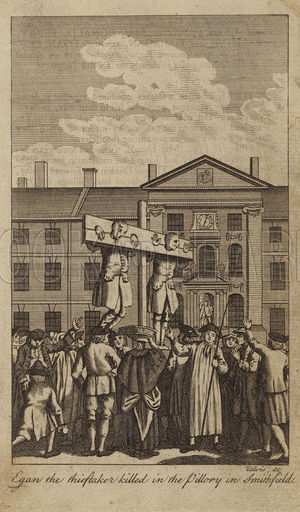

But the mood of the mob could be fickle. Sometimes their behaviour would get out of hand,

resulting in the serious injury or death of those being punished. For example, in 1751 two

men called Egan and Salmon were pilloried in Smithfield for

highway robbery prior to their imprisonment. The mob pelted

them with turnips, potatoes, stones etc to such an extent that,

in less than half an hour, Egan was struck dead by a stone, and

Salmon received injuries which later proved fatal.

The fault here arguably lay with the authorities, for using the pillory

for crimes which would normally merit hanging. Serious injuries and death were rare

where the victims were guilty of petty crimes, although minor injuries

caused by hard missiles were commonplace.

[Return to index page]

Last modified 14 May 2017.

Copyright © StocksMaster. All rights reserved.

As individual spectators were lured and frenzied by a certain malicious schadenfreude, the pillory could be interpreted as a true crowd-pleasing spectacle, but it was not merely a kind of theatre sport. Indeed it was didactic theatre; the pillory was meant to provide lessons and warnings for other would-be transgressors of the law.

As individual spectators were lured and frenzied by a certain malicious schadenfreude, the pillory could be interpreted as a true crowd-pleasing spectacle, but it was not merely a kind of theatre sport. Indeed it was didactic theatre; the pillory was meant to provide lessons and warnings for other would-be transgressors of the law.  The crowd could also be remarkably lenient to less celebrated individuals, as

this contemporary newspaper report shows:

"Yesterday at Noon Sarah Thomas stood in the Pillory in the Old Bailey,

opposite to Fleet-Lane, for keeping a disorderly House, pursuant to her Sentence

at the last Quarter Session in Guildhall. The Mob behaved to her with great Humanity,

she standing on the Pillory all the Time drinking Wine, Hot-pot, &c. It was Diversion

to her rather than a Punishment." (St. James’s Chronicle 29-31 October 1761)

The crowd could also be remarkably lenient to less celebrated individuals, as

this contemporary newspaper report shows:

"Yesterday at Noon Sarah Thomas stood in the Pillory in the Old Bailey,

opposite to Fleet-Lane, for keeping a disorderly House, pursuant to her Sentence

at the last Quarter Session in Guildhall. The Mob behaved to her with great Humanity,

she standing on the Pillory all the Time drinking Wine, Hot-pot, &c. It was Diversion

to her rather than a Punishment." (St. James’s Chronicle 29-31 October 1761)