It is a common misconception that convicted witches were always burnt at the stake. This certainly happened in

countries in which the Catholic Church held sway, where witchcraft there was viewed as a religious offence.

Images of witches and other heretics being burnt by the Holy Inquisition are dramatic, but this was by no means

a universal practice.

In Protestant countries, notably Britain and the American colonies, the attitude to witches was different.

Witchcraft was regarded as a criminal offence, and the punishments reflected this. Broadly speaking, minor

offences were punished by a combination of imprisonment and the pillory, while causing the death of others

through witchcraft was punished by hanging.

Attitudes to witches reflected social evolution. In the middle ages, witchcraft was not perceived as a serious

problem. There was no legislation relating to witches, and any local issues were dealt with by ecclesiastical

courts. Although the official religion was then Catholicism, such courts did not have the authority to impose

capital punishment.

The first Witchcraft Act

The first English law relating to witchcraft was enacted as late as 1542 by King Henry VIII. This provided

the death penalty for the practice of witchcraft, specifically:

“It shall be Felony to practice or cause to be practiced Conjuration, Enchantment, Witchcraft or Sorcery, to get

money or to consume any person in his body, members or goods, or to provoke any person to unlawful love…”

The 1542 Act was repealed in 1547 by Henry’s son, King Edward VI.

An Act against Conjuration Enchantments and Witchcrafts

A more significant anti-witchcraft law was enacted by Queen Elizabeth I in 1563. Here is a modern transcript:

“If any person shall use practice or exercise witchcraft enchantment charm or

sorcery whereby anyone shall happen to be wasted consumed or lamed in his or

her own body or member or whereby any goods or cattle of any person shall be

destroyed wasted or impaired, then every such offender, lawfully convicted, shall

on his first offence suffer imprisonment by space of one whole year without

bail…and once in every quarter of said year…shall stand openly upon the

pillory…And if any person or persons being once convicted of the same offences

as is aforesaid…does perpetrate and commit the like offence…then every such

offender…being of the said offences the second time lawfully convicted…shall

suffer pains of death as a felon and shall lose the benefit and privilege of clergy and sanctuary.”

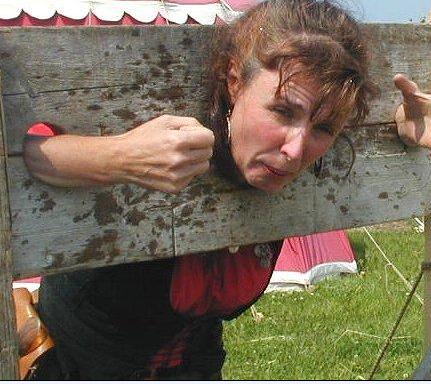

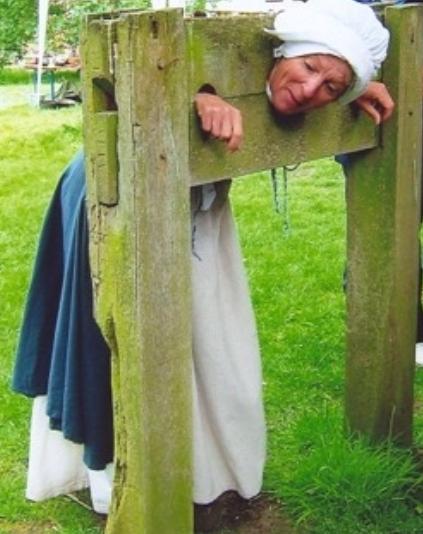

A first offence

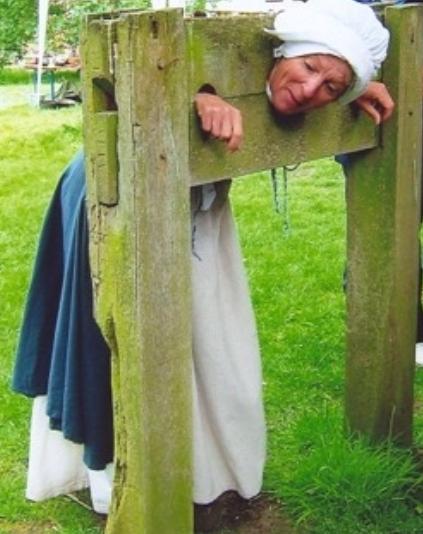

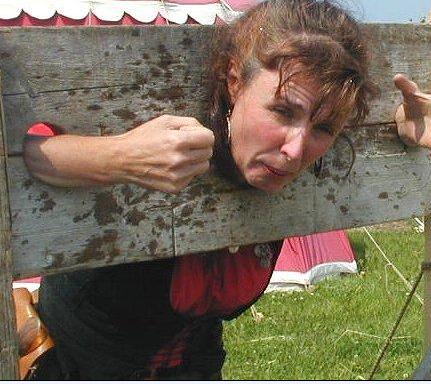

This entailed the convicted witch being pilloried for six hours, and then spending the next three months in jail.

She would then stand in the pillory again for a further six hours, but in a different town to where she had

previously been pilloried. The witch would then be returned to jail for a further three months, then pilloried

again in yet another town. Another three months in jail, followed by her final stint in the pillory in a fourth

town. After a further three months in jail, she would be released.

This entailed the convicted witch being pilloried for six hours, and then spending the next three months in jail.

She would then stand in the pillory again for a further six hours, but in a different town to where she had

previously been pilloried. The witch would then be returned to jail for a further three months, then pilloried

again in yet another town. Another three months in jail, followed by her final stint in the pillory in a fourth

town. After a further three months in jail, she would be released.

This punishment put the local authorities to some trouble and expense in transporting a convicted witch to

different towns. But exposing a witch in four different pillories ensured that she would be notorious over

a very wide area. The purpose was presumably to warn as many people as possible that a potentially dangerous

witch was in the locality. And of course to make it more difficult for a witch to evade scrutiny by simply

moving to the next town.

Elizabeth Francis

In 1566 Elizabeth Francis (of Hatfield in Essex) received this punishment for bewitching a child. In 1572

Elizabeth was convicted of making a woman ill by witchcraft, and was again pilloried and imprisoned. It is

possible that the court was unaware of Elizabeth’s previous conviction, as the punishment for a second offence

should have been hanging. Elizabeth was less fortunate on a subsequent occasion, when she was hanged for

causing the death of Alice Poole by witchcraft.

It is interesting that Elizabeth was not punished for being a witch, but for the harm she had allegedly

caused to others as a result of practising witchcraft. This illustrates nicely the distinction between

criminal and ecclesiastical law in this area.

An Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft and dealing with evil and wicked spirits

King James I was vehemently opposed to any form of witchcraft. His book 'Daemonologie', was a strong

warning against witchcraft and demonic magic. On his accession to the throne, James lost no time in

replacing the 1563 Act with the Witchcraft Statute of 1604.

This legislation increased the punishments for witchcraft. In particular it provided for the death sentence

for a first conviction of malevolent witchcraft, regardless of whether or not a victim had died. It also

became a crime to exhume bodies for magical purposes. The penalty for divining and concocting love potions

remained the pillory and a year in jail.

The 1604 Act also made it a felony to conjure, consult, entertain, covenant with, employ, feed or reward

any evil spirit for any purpose, thus introducing the concept of a pact with the Devil into English law.

Here is an extract from the original text of the 1604 Act:

“…..if any pson or psons shall from and after the saide Feaste of Saint Michaell the Archangell next

cominge, take upon him or them by Witchcrafte Inchantment Charme or Sorcerie to tell or declare in what

place any treasure of Golde or silver should or had in the earth or other secret places, or where Goodes

or Thinges loste or stollen should be founde or become ; or to the intent to Pvoke any person to unlawfull

love, or wherebie and Cattell or Goods of any pson shall be destroyed wasted or impaired, or to hurte or

destroy any Pson in his bodie, although the same be not effected and done : that then all and everie such

pson or psons so offendinge, and beinge therof lawfullie convicted , shall for the said Offence suffer

Imprisonment by the space of one whole yeere, without baile or maineprise, and once in everie quarter of

the saide yeere, shall in some Markett Towne, upon the Markett Day, or at such tyme as any Faire shalbe

kept there, stande openlie upon the Pillorie by the space of sixe houres, and there shall openlie confesse

his or her error and offence….”

The thinking behind this legislation was different to the 1563 Act. It no longer focused on the criminal

consequences of practising witchcraft, but on the inherently criminal nature of witchcraft itself.

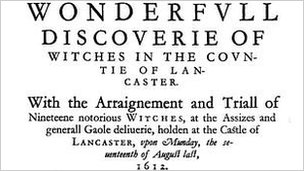

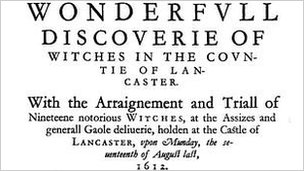

Pendle witches

The infamous Pendle witches were prosecuted under the Witchcraft Statute of 1604. In 1612, 20 people were

tried at Lancaster Assizes for witchcraft. Most of them were hanged, although a few were acquitted. Margaret Pearson

(from the nearby village of Padiham) was unusual in that she was tried for three separate offences. Margaret was acquitted

of murder by witchcraft and of bewitching a neighbour, both of which being capital charges. She was also accused

of bewitching a horse. A witness attested that Margaret had "a Spirit in the likeness of man with cloven hoofs, that she

and the Spirit had entered Dodgeon's stable through a loophole and had sat on the mare, which later died".

The infamous Pendle witches were prosecuted under the Witchcraft Statute of 1604. In 1612, 20 people were

tried at Lancaster Assizes for witchcraft. Most of them were hanged, although a few were acquitted. Margaret Pearson

(from the nearby village of Padiham) was unusual in that she was tried for three separate offences. Margaret was acquitted

of murder by witchcraft and of bewitching a neighbour, both of which being capital charges. She was also accused

of bewitching a horse. A witness attested that Margaret had "a Spirit in the likeness of man with cloven hoofs, that she

and the Spirit had entered Dodgeon's stable through a loophole and had sat on the mare, which later died".

On 19 August 1612, Margaret Pearson was convicted of bewitching the unfortunate Mr Dodgeon's horse. Her sentence (according

to the court records) was: “You shall stand vpon the Pillarie in open Market, at Clitheroe, Paddiham, Whalley, and Lancaster, foure Market dayes,

with a Paper vpon your head, in great Letters, declaring your offence, and there you shall confesse your offence, and

after to remaine in Prison for one yeare without Baile, and after to be bound with good Sureties, to be of the good behauiour.”

Being pilloried on market days was a more severe punishment. Large numbers of people would have travelled to these

(otherwise quiet) towns and villages to buy and sell livestock and other goods. The prospect of seeing a real life witch (safely locked up in a pillory)

would also have been a considerable attraction. Its fair to assume that the crowds would not have treated Margaret Pearson gently.

Being pilloried on market days was a more severe punishment. Large numbers of people would have travelled to these

(otherwise quiet) towns and villages to buy and sell livestock and other goods. The prospect of seeing a real life witch (safely locked up in a pillory)

would also have been a considerable attraction. Its fair to assume that the crowds would not have treated Margaret Pearson gently.

The last witchcraft trial in Ireland took place in 1711. Eight women (Janet Mean, Janet Latimer, Janet Millar,

Margaret Mitchel, Catharine M'Calmond, Elizabeth Seller, Janet Liston and Janet Carson) were accused of

tormenting a young woman called Mary Dunbar through witchcraft. They were all convicted under the 1604

Witchcraft Statute and each sentenced to be imprisoned for a year, and to stand four times in the pillory

in Carrickfergus.The crowd were “much exasperated against these unfortunate persons, who were severely pelted in the pillory,

with boiled cabbage stalks, and the like, by which one of them had an eye beaten out."

The 1604 Act remained in force in England until 1735 and in the American colonies until 1695. On December 14,

1692, the Massachusetts General Council endorsed the 1604 Act to give "more particular direction in the

execution of the law against witchcraft". The Salem witch trials were mostly indictments under the 1604 Act.

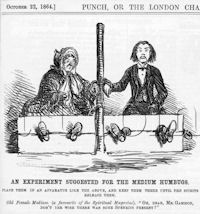

Witchcraft Act 1736

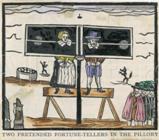

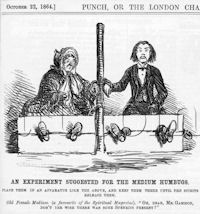

This legislation reveals a complete change in attitude, reflecting a (relatively) more enlightened age.

The Act was aimed at those who pretended to have the power to call up spirits, or foretell the future, or

cast spells. By this time, very few people (and certainly not the authorities) believed in witchcraft. The

1736 Act was essentially anti-fraud legislation, intended to protect the gullible from cheats and tricksters.

Here is an extract from the 1736 Act:

This legislation reveals a complete change in attitude, reflecting a (relatively) more enlightened age.

The Act was aimed at those who pretended to have the power to call up spirits, or foretell the future, or

cast spells. By this time, very few people (and certainly not the authorities) believed in witchcraft. The

1736 Act was essentially anti-fraud legislation, intended to protect the gullible from cheats and tricksters.

Here is an extract from the 1736 Act:

“And for the more effectual preventing and punishing of any Pretences to such Arts or Powers as are before

mentioned, whereby ignorant Persons are frequently deluded and defrauded; be it further enacted by the

Authority aforesaid, That if any Person shall, from and after the said Twenty-fourth Day of June, pretend to

exercise or use any kind of Witchcraft, Sorcery, Inchantment, or Conjuration, or undertake to tell Fortunes,

or pretend, from his or her Skill or Knowledge in any occult or crafty Science, to discover where or in what

manner any Goods or Chattels, supposed to have been stolen or lost, may be found, every Person, so offending,

being thereof lawfully convicted on Indictment or Information in that part of Great Britain called England,

or on Indictment or Libel in that part of Great Britain called Scotland, shall, for every such Offence, suffer

Imprisonment by the Space of one whole Year without Bail or Mainprize, and once in every Quarter of the said

Year, in some Market Town of the proper County, upon the Market Day, there stand openly on the Pillory by the

Space of One Hour, and also shall (if the Court by which such Judgement shall be given shall think fit) be

obliged to give Sureties for his or her good Behaviour, in such Sum, and for such Time, as the said Court shall

judge proper according to the Circumstances of the Offence, and in such case shall be further imprisoned until

such Sureties be given."

manner any Goods or Chattels, supposed to have been stolen or lost, may be found, every Person, so offending,

being thereof lawfully convicted on Indictment or Information in that part of Great Britain called England,

or on Indictment or Libel in that part of Great Britain called Scotland, shall, for every such Offence, suffer

Imprisonment by the Space of one whole Year without Bail or Mainprize, and once in every Quarter of the said

Year, in some Market Town of the proper County, upon the Market Day, there stand openly on the Pillory by the

Space of One Hour, and also shall (if the Court by which such Judgement shall be given shall think fit) be

obliged to give Sureties for his or her good Behaviour, in such Sum, and for such Time, as the said Court shall

judge proper according to the Circumstances of the Offence, and in such case shall be further imprisoned until

such Sureties be given."

No longer were people to be hanged for consorting with evil spirits. The sole punishment was a year in jail

with four appearances in the pillory. And the time in the pillory was reduced from six hours to one hour on

each occasion.

According to the Newcastle General Magazine (published 26 April 1758), on 11 April "Susannah Fleming, stood in the pillory at the White

cross, Newcastle, one hour, pursuant to her sentence, for the first time,

(being to stand once a-quarter, for a year,) for fortune telling.

Though not molested by the populace, she was nearly strangled before

the time was expired, occasioned either by her fainting and shrinking

down, or from having too much about her neck, and being thereby

straightened in the hole. A sailor, out of charity, brought her down

the ladder upon his back, in a nearly dying state."

According to the Newcastle General Magazine (published 26 April 1758), on 11 April "Susannah Fleming, stood in the pillory at the White

cross, Newcastle, one hour, pursuant to her sentence, for the first time,

(being to stand once a-quarter, for a year,) for fortune telling.

Though not molested by the populace, she was nearly strangled before

the time was expired, occasioned either by her fainting and shrinking

down, or from having too much about her neck, and being thereby

straightened in the hole. A sailor, out of charity, brought her down

the ladder upon his back, in a nearly dying state."

Helen Duncan

In 1944, Helen Duncan was the last person to be jailed under the Witchcraft Act, on the grounds that she

had pretended to summon spirits. She came to the attention of the authorities after supposedly contacting a

sailor of HMS Barham whose sinking was hidden from the general public at the time. Helen was prosecuted under

the Witchcraft Act because the authorities allegedly feared that she would reveal their secret plans for the

D-Day invasion.

In 1944, Helen Duncan was the last person to be jailed under the Witchcraft Act, on the grounds that she

had pretended to summon spirits. She came to the attention of the authorities after supposedly contacting a

sailor of HMS Barham whose sinking was hidden from the general public at the time. Helen was prosecuted under

the Witchcraft Act because the authorities allegedly feared that she would reveal their secret plans for the

D-Day invasion.

Following Helen’s conviction, the 1736 Act still required that she should stand in the pillory on four occasions.

Fortunately for her, the pillory had been abolished in 1837. Helen spent nine months in prison.

Fraudulent Mediums Act

The 1736 Witchcraft Act was repealed in 1951, and replaced by the Fraudulent Mediums Act.

Being pilloried on market days was a more severe punishment. Large numbers of people would have travelled to these

(otherwise quiet) towns and villages to buy and sell livestock and other goods. The prospect of seeing a real life witch (safely locked up in a pillory)

would also have been a considerable attraction. Its fair to assume that the crowds would not have treated Margaret Pearson gently.

Being pilloried on market days was a more severe punishment. Large numbers of people would have travelled to these

(otherwise quiet) towns and villages to buy and sell livestock and other goods. The prospect of seeing a real life witch (safely locked up in a pillory)

would also have been a considerable attraction. Its fair to assume that the crowds would not have treated Margaret Pearson gently.

This entailed the convicted witch being pilloried for six hours, and then spending the next three months in jail.

She would then stand in the pillory again for a further six hours, but in a different town to where she had

previously been pilloried. The witch would then be returned to jail for a further three months, then pilloried

again in yet another town. Another three months in jail, followed by her final stint in the pillory in a fourth

town. After a further three months in jail, she would be released.

This entailed the convicted witch being pilloried for six hours, and then spending the next three months in jail.

She would then stand in the pillory again for a further six hours, but in a different town to where she had

previously been pilloried. The witch would then be returned to jail for a further three months, then pilloried

again in yet another town. Another three months in jail, followed by her final stint in the pillory in a fourth

town. After a further three months in jail, she would be released.  The infamous Pendle witches were prosecuted under the Witchcraft Statute of 1604. In 1612, 20 people were

tried at Lancaster Assizes for witchcraft. Most of them were hanged, although a few were acquitted. Margaret Pearson

(from the nearby village of Padiham) was unusual in that she was tried for three separate offences. Margaret was acquitted

of murder by witchcraft and of bewitching a neighbour, both of which being capital charges. She was also accused

of bewitching a horse. A witness attested that Margaret had "a Spirit in the likeness of man with cloven hoofs, that she

and the Spirit had entered Dodgeon's stable through a loophole and had sat on the mare, which later died".

The infamous Pendle witches were prosecuted under the Witchcraft Statute of 1604. In 1612, 20 people were

tried at Lancaster Assizes for witchcraft. Most of them were hanged, although a few were acquitted. Margaret Pearson

(from the nearby village of Padiham) was unusual in that she was tried for three separate offences. Margaret was acquitted

of murder by witchcraft and of bewitching a neighbour, both of which being capital charges. She was also accused

of bewitching a horse. A witness attested that Margaret had "a Spirit in the likeness of man with cloven hoofs, that she

and the Spirit had entered Dodgeon's stable through a loophole and had sat on the mare, which later died".

This legislation reveals a complete change in attitude, reflecting a (relatively) more enlightened age.

The Act was aimed at those who pretended to have the power to call up spirits, or foretell the future, or

cast spells. By this time, very few people (and certainly not the authorities) believed in witchcraft. The

1736 Act was essentially anti-fraud legislation, intended to protect the gullible from cheats and tricksters.

Here is an extract from the 1736 Act:

This legislation reveals a complete change in attitude, reflecting a (relatively) more enlightened age.

The Act was aimed at those who pretended to have the power to call up spirits, or foretell the future, or

cast spells. By this time, very few people (and certainly not the authorities) believed in witchcraft. The

1736 Act was essentially anti-fraud legislation, intended to protect the gullible from cheats and tricksters.

Here is an extract from the 1736 Act:

In 1944, Helen Duncan was the last person to be jailed under the Witchcraft Act, on the grounds that she

had pretended to summon spirits. She came to the attention of the authorities after supposedly contacting a

sailor of HMS Barham whose sinking was hidden from the general public at the time. Helen was prosecuted under

the Witchcraft Act because the authorities allegedly feared that she would reveal their secret plans for the

D-Day invasion.

In 1944, Helen Duncan was the last person to be jailed under the Witchcraft Act, on the grounds that she

had pretended to summon spirits. She came to the attention of the authorities after supposedly contacting a

sailor of HMS Barham whose sinking was hidden from the general public at the time. Helen was prosecuted under

the Witchcraft Act because the authorities allegedly feared that she would reveal their secret plans for the

D-Day invasion.